When I started my family history research I never expected to find wealth. I knew that both of my parents hailed from working-class families and thought it likely that this would have been the case for my ancestors too. My parents both left school at the age of 15 to learn a trade; my grandparents younger, at 12. Grandad Rushworth told me he was always getting the cane as a child at school because he worked for a butcher and the morning deliveries he had to do meant he was often late. He had little choice; the family needed his income.

Nevertheless, while I expected my ancestors to have worked for a living and perhaps been close to the breadline I hadn’t anticipated the stories of genuine, life-threatening poverty I would turn up. The official records are stark, bald statements of fact but behind them lies a level of suffering I can only imagine.

Last time I talked about my grandad, Leo King, and the discovery that he had become an inmate of Buckley Hall orphanage with two of his brothers when the three of them were (roughly) aged 9, 11 and 13. His mother, Katherine, was still alive at the time, a widow living with older, working children and a younger daughter, so I can only speculate that her husband’s death must have affected the family finances to the point where she could no longer afford to care for everybody and had to make a choice about what to do for the best. I can’t imagine how it must feel to admit you can no longer support your children and what Katherine and her three young sons’ journey to the workhouse must have been like.

I was trying to trace Leo’s younger sister Alice who was five months old on the 1901 census but had disappeared from the available official records by 1911. Alice had a twin brother, John, who went to Buckley Hall with Leo in 1909. I had a suspicion that Alice might have already died by this time, which turns out to have been correct.

Alice Margaret Ellen King was born on 11 October 1900 with her twin brother John. In 1900 it’s unlikely that Katherine would have known she was expecting twins – there were no NHS midwife checkups, no ante-natal scans, none of the high-tech care and information that surrounds modern childbirth. This was Katherine’s seventh, possibly eighth pregnancy and the babies were born at home, at 119 Prince Street, South Manchester. Their father Thomas’s occupation is listed as ‘porter at stock exchange’ – possibly the Royal Exchange in Manchester through which the worldwide trade in Lancashire’s cotton industry was managed.

Manchester Royal Exchange, photographed in 1902. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, GB127.m56593

Alice was born at 9pm – this is the only birth certificate I have where the time of birth is recorded; I would have to order John’s as well to find out which of the twins was born first. Incidentally this is the only instance I can find of a birth certificate for any of Thomas and Katherine’s children; strange given that civil registration of birth had been a legal obligation for over 70 years.

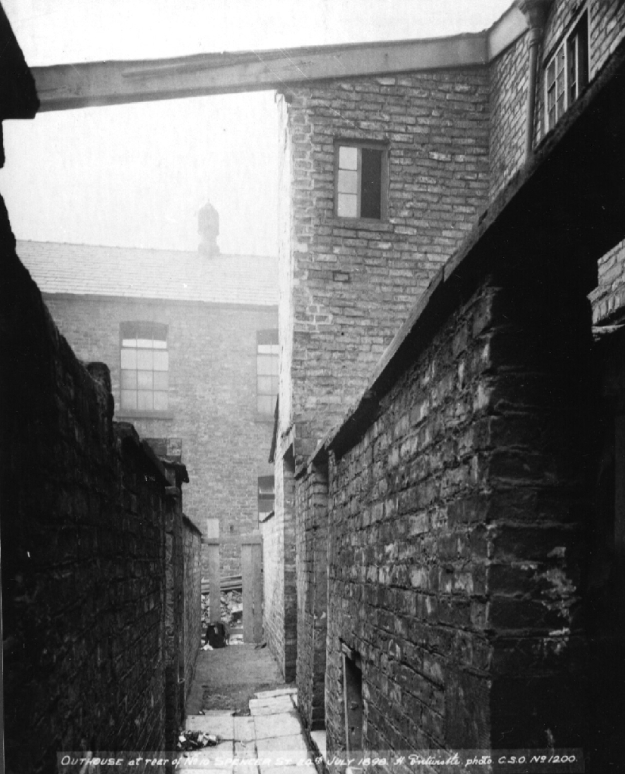

Alice lived less than a year. She died on the first of September 1901 at the family home, now 10 Spencer Street, also in South Manchester. The family were living there at the time of the 1901 census so must have moved during the first five months of Alice’s life. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives actually have a photograph of the outhouse behind 10 Spencer Street – it’s hard to see any detail but it appears to be a typical working class terraced house of the time.

The outhouse behind 10 Spencer Street, taken in 1898. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, GB127.m04605.

The cause of Alice’s death is detailed on the death certificate. She died of “Ricketts & Diarrhoea 6 days, convulsions 1 day”. Her mother Katherine was with her when she died.

Alice’s tragic death aged just 10 months old gives an insight into the family circumstances. Rickets was common in the past and often associated with poverty. It’s a condition that affects bone development in children, caused by a deficiency of vitamin D and calcium in the diet. According to Wikipedia, “the majority of cases occur in children suffering from severe malnutrition, usually resulting from famine or starvation during the early stages of childhood.”

As a poor woman in the early 20th century Katherine would have had little choice but to breastfeed her children. The challenge of feeding two babies when she might not have been in good health herself might have proved too much and contributed to Alice’s poor health – breastfeeding takes up masses of calories and if Katherine wasn’t well nourished there’s no way her babies would have been. It’s worth noting that Leo, older than Alice by two years, was small into adulthood: his RAF attestation papers from 1918, when he was 20 years old, give his height as just four feet eleven inches tall. It used to amuse us when my grandma talked about Leo’s height: I’m 5’10” and my brother 6’5″ so we used to joke about what happened to the short genes. Alice’s fate suggests that Leo’s small build was probably not down to nature but nurture, or rather lack of it; caused by poor nutrition in childhood.

The death of a baby from malnutrition just two generations ago seems shocking but is a reminder of how much we now rely on the modern welfare state and National Health Service and the extent to which they have transformed our lives. In Britain in 2016 we have support for people who can’t work through age or illness, financial support for people who are unemployed and health care free at the point of use. If Alice King had been born a century later it’s unlikely that poverty and preventable illness would have taken her life in this way. But campaigners and reformers fought hard for the ‘safety net’ offered by the welfare state and we cannot take any of it for granted.

I didn’t start this blog to be political, but my great-aunt Alice’s story acts as a reminder to be vigilant against those who seek to undermine the welfare state. The Guardian recently reported that diseases of food poverty, such as rickets, are once again on the rise. The current austerity narrative in British politics pushes an ideological position that we can only “balance the books” by cutting back on the amount of support given to people in need. The arguments that poverty is a result of behaviour and that welfare encourages dependency have been around since before the Poor Law despite not being supported by evidence. Many ordinary working people will have ancestors like mine, living just one wage packet away from destitution. Perhaps by understanding more about their lives we can learn to value what we have.