One of the most striking things about family history is the difference in family size between modern families and those in the past. Once you get back more than two generations the change is clear – instead of two, three or four children, as has been the norm from the 1940s or 50s onwards, most families have five, six, seven, even ten or more children. Historians have estimated the total fertility rate – the number of children a woman might expect to have between the ages of 15 and 39 – at 5.75 in the early decades of the 19th century. However many of my female ancestors who reached old age had a baby every other year from shortly after their marriage until the loss of their husband or the menopause, whichever came first.

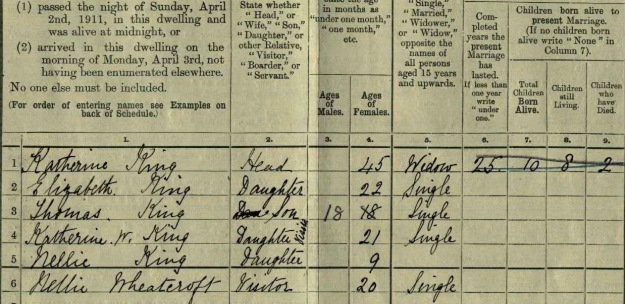

The 1911 census gives a great insight into family size and fertility a century ago because the census return form asked respondents for a specific set of information that hadn’t been included in previous censuses: how long their present marriage had lasted; how many children had been born to the marriage and how many of those children had died. I have several direct female ancestors for whom this information is recorded in 1911. Their data look like this:

- Katherine King (great-grandmother): 45 years old and widowed. She had been married for 25 years and had 10 children, of whom 8 were still living and two had died. She had four of her children living with her, aged between 9 and 22. I’ve written about Katherine and her children, including my grandfather Leo, in previous posts.

- Minnie Louisa Dodsworth (great-grandmother): 26 years old and married for six years. She had had four children in that time but only one had survived, a three-year-old daughter Ida who was my grandmother’s older sister.

- Alice Ellis (great-great-grandmother): aged 40, she had been married for 15 years and had had eight children, seven of whom were still living and aged between 1 and 14 years.

- Mary Ann Rushworth (great-great-grandmother): also aged 40, she had been married for 17 years and had 8 children, all of whom had survived and were aged between 1 and 17.

- Fanny Brayshaw (great-great-grandmother): she was 33 years old and widowed. She had been married for 11 years and had five children, of whom one had died.

- Harriet Jenkins (great-great-grandmother): 34 years old and married for 13 years. 9 children born of whom two had died.

- Sarah Jane Boyce (3rd great-grandmother, via my maternal grandfather Edward Rushworth): 57 years old and married for 38 years. Sarah-Jane had had an impressive 15 children, of whom 10 were still living. I know of 11 of those children through census records and can have a rough guess at the dates when other siblings were born by looking for gaps between the known births. Sarah Jane had the most children of any ancestor I’ve found so far.

These figures are striking because of the difference between the lives lived by my female ancestors and the facts of family life today. Only one of the seven women – Mary Ann Rushworth – had reached her 40s without losing a child. Sarah Jane Boyce’s 15 children would be very unusual in 2016, as would the fact that a third of those children died, probably very young. Equally Minnie Dodsworth’s loss of three of her four children born within just six years would be a shocking tragedy. It’s also likely that census records underplay the extent of child mortality. While the 1911 census gives a helpful insight into family size and child mortality, it only records the fate of those children who were born alive. I can only guess at possible instances of stillbirth or miscarriage.

These stories raise many questions about the extent to which women’s lives in the past were shaped by childbearing, child rearing and loss. Few of my female ancestors had an occupation recorded in the census after they married, probably because they had frequent pregnancies and always had young children in the home. The physical impact of subsequent pregnancies and births must have been significant, particularly before modern medicine (I have yet to find an ancestor who died in childbirth, but the statistical evidence of maternal mortality during the 19th century is eye-watering). The emotional impact, too, not just of the actual and potential loss of young children but of the relentless demands of decade upon decade of child-rearing, must have been significant for both women and men. I have not yet found a childless marriage in my family history, but in past societies where large families were the norm and the expectations of women were defined by their roles as wives and mothers, infertility must have been at least as traumatic as it is now.

Historical records only give facts, and often only partial ones at that. Part of the challenge of family history is trying to fill in the gaps using inference, contextual research and sometimes imagination. It seems plausible that our ancestors’ relationships, whether marital relationships or those between parents, children and siblings, were very different from our own.