Family history can become a fairly tedious list of names, dates and places, with very little turning up in the records to add context or colour. But just occasionally something leaps out to add detail to an otherwise anonymous ancestor’s life.

James Wood was my great-great-great-great-grandfather on my mum’s side. The body part in question features in a surgeon’s report from the 5th page of James’s army discharge papers dated 1839. Now I will confess that I have had this record saved to my computer for well over a year. I had skimmed it, determined it was repetitive, discovered the handwriting was difficult to read, and filed it away for later on the mistaken assumption that it would contain nothing very unusual. Lesson learned.

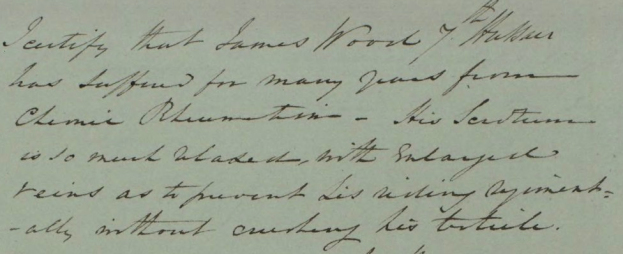

Here’s an extract from the army surgeon’s report:

And this is my best attempt at a transcript.

“I certify that James Wood 7thHussars has suffered for many years from Chronic Rheumatism. His scrotum is so much [?] with enlarged veins as to prevent his riding Regimentally without crushing his testicle and he is considered by the commanding officer unfit for the active duties of a soldier in which opinion I concur. His disabilities are the effect of Constitutional Infirmity and not of vice or Intemperance. His conduct in Hospital has always been good.”

Poor James. At least they didn’t think he had venereal disease. The army has long been concerned with ‘vice or intemperance’ in its ranks, with good reason.

James was born in Leeds around 1798. He joined the 22nd Light Dragoons in 1815, when he was 17, transferring after a year to the 7th Hussars. His discharge papers include the original attestation record from when he joined the regiment. It records that he was five feet six and three-quarter inches tall, had a fresh complexion, grey eyes and light brown hair. He was also illiterate, leaving a mark instead of a signature – something that he did again when he left the army 23 years and 170 days later. Evidently his army training didn’t include learning to write.

17-year-old James was a cropper by trade. A cropper was a skilled worker in the textile industry, responsible for finishing woollen cloth by ‘cropping’ the nap using a huge pair of shears (the Leeds City Museum has a pair on display, I was surprised at how big they are). The Luddite riots were in full swing in the early 19th century in response to technological developments of the Industrial Revolution. Workers in the woollen trade, particularly croppers and weavers, protested the loss of their livelihoods as textile manufacturers began to introduce efficient new machinery that was quicker and cheaper than employing skilled men. The Luddites became violent, smashing machinery and even committing murder. In 1812, three years before James joined the army, 17 men were hanged in York for the new crime of machine-breaking, and a further 60 were tried the following year in what was widely seen as a show trial. While the violence had died down by 1815, skilled textile workers didn’t stand a chance of maintaining their livelihoods in the face of rapid industrial developments. James may well have decided to cut his losses. He enlisted in the military for the sum of six pounds.

Both the 22nd Dragoons and the 7th Hussars had been involved in the Napoleonic Wars, fighting with Wellington against the French. Perhaps the army also offered a more glamorous lifestyle than staying in Yorkshire and cropping woollen cloth. The British Library cites Jane Austen’s 1813 novel ‘Pride and Prejudice’ as a prime example of the glamour attached to military men at this time. Alongside Colin Firth’s wet shirt, the story features a couple of breathless teenage girls who chase charming but dastardly soldiers around the countryside and nearly ruin their families in the process. While it’s unlikely that the illiterate James Wood ever read ‘Pride and Prejudice’, he may well have been swayed by the level of female attention men in uniform could attract on the streets of Leeds.

So back to James’s scrotum. I’d wondered, from the way the medical report is written, whether the rheumatism mentioned in the previous sentence might have caused his problem. According to Alan Humphries, the Thackray Medical Museum‘s highly knowledgeable librarian, they were probably two separate conditions. The Arthritis Foundation rather unhelpfully tells me that the term ‘rheumatism’ is no longer in use but that historically it referred to a range of muscle and joint conditions. The Hussars was a mounted regiment, meaning that James would have been in the saddle for a lot of his 23 years. That in itself might have been enough to cause the ‘enlarged veins’ in the scrotum referred to in the report. It seems that James was discharged from the army on health grounds, though he might have felt by then that he had served his time. The record gives very little information on his actual military service. It states that he served in France from 1815 until 1818, where he was presumably part of the occupying army after Wellington’s victory at Waterloo, and the rest of his time ‘at home’.

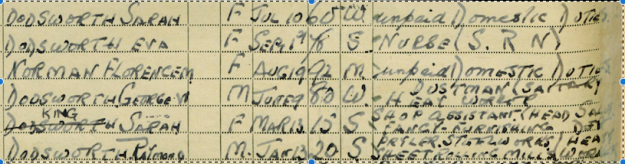

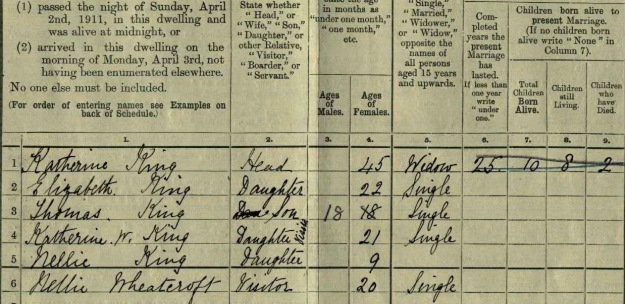

We shouldn’t feel too sorry for James, despite his unfortunate ailment (and the fact that even death isn’t enough to keep his genitals from appearing on the internet without his consent). He married Isabella Mackie on 29 September 1833 at Hamilton, Scotland, and fathered at least 7 children between 1835 and Isabella’s death in 1850 (she died aged 37 of ‘disease of the brain’, but that story will have to wait for another day). Five of the children were born after 1839 when the scrotum condition was diagnosed. It clearly didn’t do him any lasting damage. He appears on the censuses in 1851, 1861 and 1871, working in a range of horse-related jobs (groom and coachman, for example). Helpfully one of the censuses lists him as a ‘Chelsea Pensioner’, meaning he was entitled to a military pension. This is the only reason I knew to look for a military record in the first place.

On 20th February 1867 James’s daughter Elizabeth Harriet Wood married my mum’s great-great-grandfather Haydon Rushworth at Leeds parish church. This time both bride and groom signed their names.