We recently celebrated the 100th birthday of my oldest living relative. Auntie Joan isn’t strictly my auntie – she’s my grandad’s cousin, which makes her my second cousin twice removed, but who knows what that means, and ‘second cousin twice removed Joan’ hardly trips off the tongue. So Auntie Joan it is. My mum has had a close relationship with Joan for over 60 years so she has always been a part of my life.

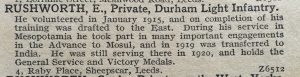

Joan has dementia now so conversation is limited but she can still tell stories about the past. She talks a lot about her parents, Lily and William, who met through the Salvation Army just after the First World War. In 1936, when Joan was almost 15, her dad took her to watch the Jarrow Marchers as they passed through Leeds. It clearly made an impression on her – 80 years later she could still remember how worn and ragged-looking the marchers were.

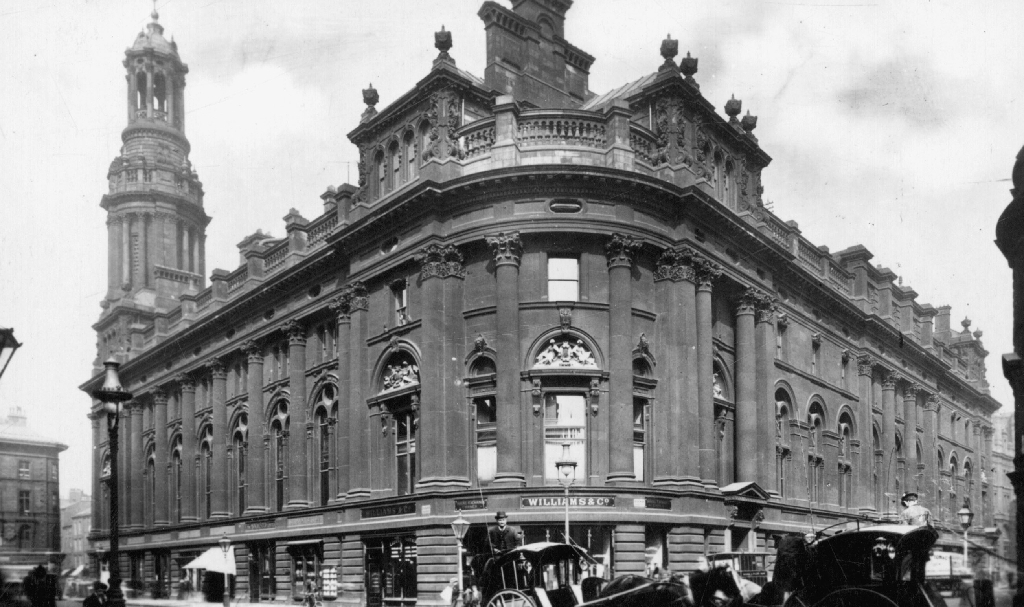

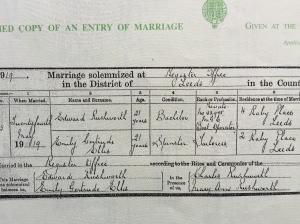

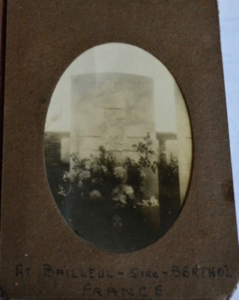

Joan and I are related through her father, William Ellis, and my grandad’s mother Emily who were siblings. Our common ancestors, their parents William Ellis and Alice Martha Boyce, married in 1896 at Leeds Parish Church, now Leeds Minster. They are both listed on their marriage certificate at addresses in Church Lane, which is not the first time I’ve found couples marrying who lived within a few streets of each other. William, aged 29, was employed as a groom at the time of his marriage. 24-year-old Alice is flatteringly described as a ‘spinster’ and no profession is listed for her.

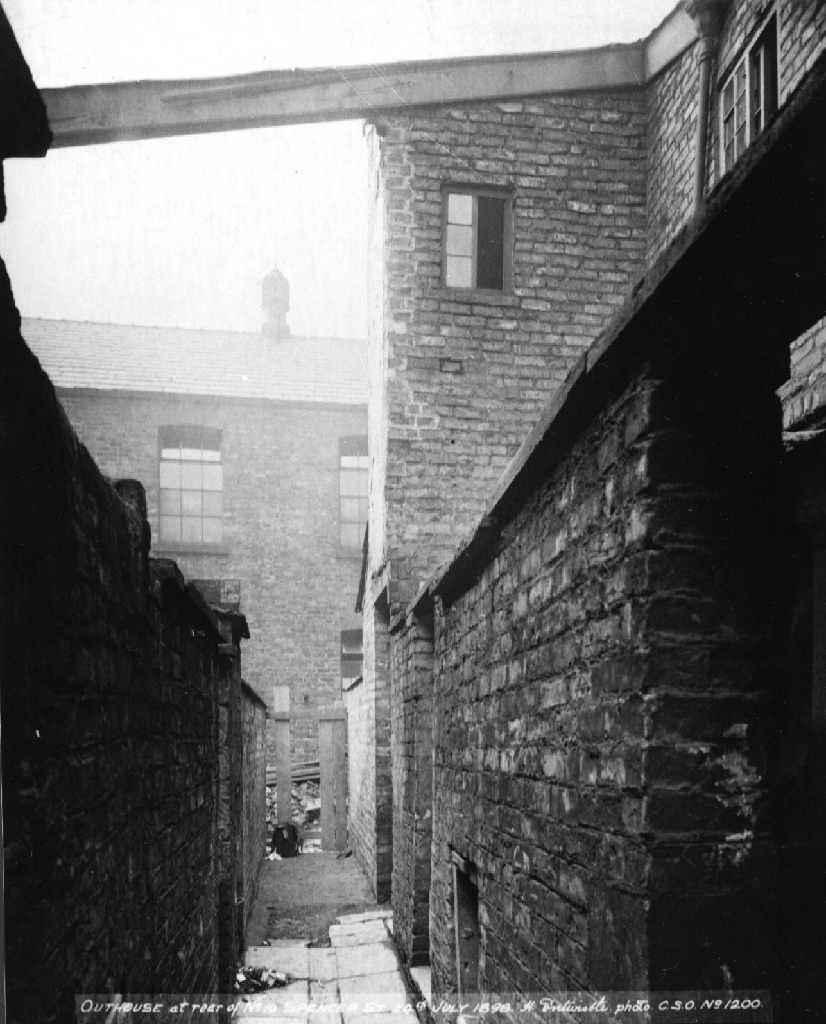

Neither of them was native to Leeds: William was born in Liverpool and Alice in Tyd St Giles, a farming community in Cambridgeshire near the Norfolk border. I’m often surprised by how much my mostly working class ancestors seem to have moved around the country during their lives. Alice’s father was a labourer and they moved frequently around rural Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire, presumably following agricultural work. Three years before she married, in the 1891 census, Alice was living in Leighton in Huntingdonshire as the ‘general servant’ of 70-year-old farmer Benjamin Prior and his wife Elizabeth. I could speculate that she might have moved to Leeds for a service position and met William there.

The Ellis family had moved from Liverpool to Otley by 1881, where William’s father was running a tobacconist’s shop. I haven’t found William in the 1891 census so I can’t fathom what he was doing in young adulthood or how he and Alice might have met. After their marriage William seems to have remained in working class occupations during his lifetime, variously caring for horses and later working as a ‘car washer’ on the Leeds City Tramway. Alice and William had eight children together, of whom seven survived – including my great-grandmother Emily and Joan’s father William.

It’s really thanks to Auntie Joan that I have been able to trace my mum’s family tree. Joan had a phenomenal memory until Alzheimer’s stole it from her, and seemed to know the business of everyone in the family no matter how distantly related they were. Some years ago she wrote me a list of female ancestors together with their maiden names that she’d gathered together from family Bibles belonging to the many cousins she kept in close contact with. Maiden names are gold dust when you’re searching census and BMD records – knowing them short-cuts a lot of uncertainty wading through multiple records of people who might be your ancestors but equally might not. Joan also had a deeply irritating habit of alluding to potential scandal in the family history but then refusing to say any more. I’ll just have to keep searching for that.

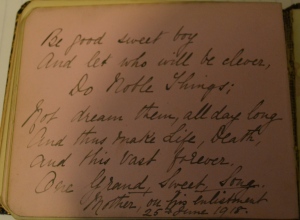

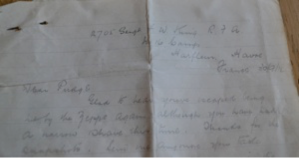

There is one tantalising anecdote that came to me via Joan. It relates to Alice’s Boyce’s mother, Sarah Jane Foster, who was born about 1855 in Tyd St Giles, Cambridgeshire and was my great-great-great-grandmother. Joan had an older relative who wrote her the following in a letter:

“I can just remember as a child when we were still living in London visiting Great Grandma Foster who lived at Boston in Lincolnshire. She only had one eye, the other was ruined by a leech which was used to supposedly cure her headaches. I believe leeches were used a lot in those days”.

It’s hard to imagine how grim it must have been to have your sight damaged in that way – particularly given that, far from suing for medical negligence, Sarah Jane would likely have paid some kind of unofficial medical practitioner for the privilege. And she probably still had headaches. There’s obviously nothing in the formal records to indicate that she had this disability – for her, as for the majority of working class lives, there’s only the bare bones of births, marriages, deaths and census records and very little to add colour to ancestors’ lives. Thanks to Auntie Joan, her curiosity and connections, this detail has survived.